Feminist values are central to many food sovereignty and agroecology movements. Feminisms that bring an anti-colonial, decolonial or indigenous perspective work to reconstitute non-hierarchical relationships among people, between people and nature, and through this shift, the relationship between people and their food. This article is a part of our column, Agroecology in Motion: Nourishing Transformation.

There are so many feminisms. Intersectional feminism, Black feminism, Indigenous feminism, African feminism, Muslim feminism, communitarian feminism, autonomous feminism, ecofeminism, decolonial feminism — these are just a few current feminisms from the list. Each movement emerges from different historical, geographical and socio-cultural-political contexts. What all of these feminisms have in common is the aim to confront patriarchal, structural inequality and systematic discrimination against non-male genders. Foodways are one place in which this confrontation is front and center.

Feminism is a word that carries heavy historical baggage. The word has been stigmatized, still commonly associated with man-hating white women, a sexist stereotype in itself. But today, in what is considered to be the ‘fourth wave’ of feminism, it is gaining ground as a mobilizing concept across the world. People who never considered their actions, thoughts or attitudes as feminist are beginning to identify with the word, and those who never saw feminist issues to be important are beginning to realize that they have deep personal meaning and profoundly important political implications. Similarly, food activists are embedding feminist approaches and values in social movements. For many, feminism is seen to be a fundamental part of agroecology and food sovereignty.

This blog is an exploration into what it is that intertwines feminisms with agroecology and food sovereignty. It highlights how a decolonial gaze on gender and feminism, primarily from North and South America (referred to as Turtle Island and Abya Yala respectively to substitute the colonial name America) helps to fill in historical gaps, and the potential of this perspective for nurturing feminist food movements today.

Image source: https://www.indigenousgoddessgang.com/

We are a group of European and North American scholar activists working on agroecology and food sovereignty at the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience at the University of Coventry in the UK. We work as allies in solidarity with social movements, farmers’ organisations, and citizens’ groups around the world for a radical transformation of our food systems based on the principles of agroecology and food sovereignty. As women, men, mothers, immigrants, members of ethnic minorities, as individuals and as a collective, we carry with us our own baggage of oppression that fuels our participation in these emancipatory movements. Aware of the complexity and the delicate, highly political and deeply painful nature of decolonial work, we wish to express our deep commitment to support this movement.

Feminisms of all types are emancipatory movements, but the first emancipation is from one’s own internalized patriarchy. It is an intensely personal process of unlearning and reprogramming that must be made collective. Feminist agroecologies and decolonial feminisms offer a path forward that meets each person and community where they are in their own personal and collective process.

Feminisms in agroecology and food sovereignty

Agroecology is being proposed as a sustainable alternative to industrial farming models. Some versions of agroecology focus on farming practices and don’t intend to question the status quo of unjust power relationships in foodways. However, many agroecology and food sovereignty movements that emerge from the grassroots are focused on social justice and try to keep feminist values central. In certain spaces it is now common to hear, for example, ‘without feminism, there is no agroecology’[1].But why?

Social movements across the world are mobilizing around the idea that ‘without feminism there is no agroecology’.

One reason is the crucial role that women play in agriculture as seed keepers, domesticators of plants and breeds, and guardians of diversity. Women are creative food preservers, masters of nutrition, and transmitters of rooted history through their recipes and stories. Women secure and prepare food for their households and communities, they are caretakers, have agency, bring innovative change and build alternatives and social movements, yet they are largely excluded from economic opportunities and governance spaces.

However, feminism is not exclusively about or for women, nor do the movements stop at gender equality. Gender equality is an important first step, especially in contexts and cultures where women regularly suffer explicit abuse and subordination, but the convening power of feminism lies in the values that feminist movements represent. Likewise, the values at the heart of feminisms are what ties it closely to agroecology and food sovereignty. These three movements are intertwined emancipatory movements and political projects that fight for autonomy, self-determination, egalitarianism, epistemic reconstitution and social justice.

Putting it plain and simple: food sustains life. Agroecology and food sovereignty are ways of relating to food that nurtures bodies, communities and the environment, generation after generation. Agroecology is about caring for the soils, for water, for the life cycles of microorganisms, insects and other animals of the agroecosystem, for seed and plant as well as breed biodiversity, and for the people who work the land, as well as those who process, transport and eat the food. Feminisms at the core of agroecology and food sovereignty aim to keep life, and the reproduction of life, at the heart of their concerns.

In the case of agroecology, ‘life’ refers to the health of the natural and social ecosystems that humans and their wellbeing form a part of, in which access to food for everyone is central. Feminist practices nurture a spiderweb of interdependencies and relationships that generate social resilience. This approach stands in striking contrast with food as a commodity guided by lineal thinking, actions, decisions and relationships based on domination, profit or individual, short-term gain.

Feminist agroecologies place the interconnectedness of people and nature at the center of economic and political systems. Producing food in a way that nurtures relationships of equality requires accounting for the invisible care work that goes on in the fields and behind closed doors. What is invisibilized about care work is not only the work itself, but the way in which healthy communities and families are built on the backs of this work. Feminist agroecologies recognize that what is considered ‘productive work’, such as selling cash crops, is not more important than the work of reproduction, such as producing food for household consumption.

Learning from decolonial feminisms

Feminist movements that are anti-racist, decolonial, anti- and post-colonial, including indigenous feminism, offer other ways of thinking about the link between feminism and food. Specifically borne from the context of Turtle Island and Abya Yala, decoloniality offers a particularly powerful lens.

Coloniality refers to relations of power that have emerged as a result of colonialism but persist in modern society[2]. Coloniality asserts that some people are superior and others inferior. Under colonialism, non-white people were considered inferior to white Europeans and women were seen to be inferior to men. The rich expression of non-binary genders was erased and shamed, leaving room only for heteronormativity. Beliefs that embedded ‘otherness’, inferior and superior, were, and are, used as tools to separate and validate colonial relations. This pervasive culture of hierarchy, discrimination, domination and control persists in contemporary structures of knowledge and culture, as well as in many social and labour structures. Feminism, when seen from this perspective, is about undoing historical harm and reclaiming space for women, as well as for people of other non-male genders, and of black, brown and red skin in particular. The concept of gender itself is seen to be a colonial invention of subordination[3]. Intersectionality points to the way these structures of power affect people who do not fall in the category of cis white males through discrimination based on sexism and how this cannot be understood separately from racism, classism and other forms of structural discrimination[4].

Decoloniality proposes a ‘decolonisation of the mind’[5] in which ways of knowing and being are ‘delinked’ from the colonial/modern project[6], including revaluing culture, language and spirituality. In the context of agriculture, feminisms that bring an anti-colonial, decolonial or indigenous perspective work to reconstitute non-hierarchical relationships among people, between people and nature, and through this shift, the relationship between people and their food.

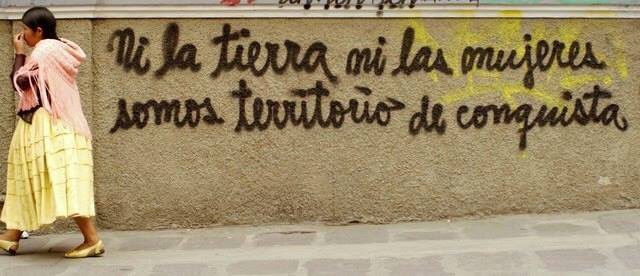

There is a tight link between the development of the colonial concept of gender, and that of the colonial concept of nature in which exploitation of both became necessary for the capitalist project. Colonialism brought with it extractive capitalist thinking which permitted contamination and degradation of land and water and estranged people from nature. Women, similarly, were, and in some places continue to be treated as subjugated property. Decolonial feminisms recognize that the health of the earth is fundamental to the health of all human and non-human beings, and that the relationships people keep with natural ecosystems are part and parcel of who they are, not something secondary or optional. Decolonial feminist struggles focus both on defending territory as land, as well as bodies. ‘Neither land nor women are territory to be conquered’ is a phrase used among activists in Latin America and Spain.

¡Neither land nor women are territory for conquest!

Another powerful weapon of colonialism is the disruption of indigenous economic structures, for example, the abolition of systems of collective land management and practices of solidarity, exchange and mutual support. Decolonial feminisms represent a pathway that shifts away from individualized thinking and acting to nurturing the collective wellbeing; it is a shift from the nuclear family, family farming and the cookie cutter model of monogamous and heteronormative relationships to networks of functional, supportive communities. Agroecology as a model for agriculture, in fact, holds its transformational potential as collective action at the territorial level. One farm alone can’t make a dent in the industrial food system, but working collectively, functioning as an ecosystem, many actors together in a territory that all place ‘life’ in the center have a fair chance.

The doors that decolonial perspectives open for activists, scholars and others, with respect to agroecology and food sovereignty, is a reinterpretation of history that helps us to understand the harm done to bodies and territories by historical colonialism, and today through pervasive coloniality. Decolonial practice is to delegitimize these notions of coloniality and to decolonize relationships: relationships with oneself, with others, with spirituality, with food and with the earth. ‘Decolonizing relationships’ implies recognizing that a diverse range of ways of thinking, being and knowing are valid; that there is no one ‘right way’, and no separation, superiority or inferiority where we have been taught to see it. Decolonial feminism is a practice in which we are faced with the task of erasing mental divides and hierarchies imposed on us, including production over reproduction, industry over nature, minds over bodies, and urban over rural. This includes reviewing the false division between food and medicine, climate justice, social justice and food justice. It is about working together across movements, and celebrating the power of diversity, not repressing it.

Some recent articles in English:

- Indigenous Feminism Is Our Culture by Jihan Gearon (2021)

- Women’s Power in Food Struggles. The Right to Food and Nutrition Watch (2020)

- The path to feminist agroecology by Marta Soler Montiel, Marta Rivera-Ferre and Irene García Roces (2020)

- Care and sustainability of life: dialogues between feminist agroecology and political ecology by Diana Lilia Trevilla Espinal and Maritza Islas Vargas (2020)

- Indigenous Environmental Network Webinar Series: Feminisms and Indigenous Women (2020)

- Without Feminism there Is no agroecology: Towards healthy, sustainable and just food systems by Civil Society and Indigenous Peoples’ Mechanism (CSM ) for relations with the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS) working group of women (2019)

- Understanding feminism in the peasant struggle by La Via Campesina (2017)

- Feminism is Not About Gender Equality by RadFemFatale (2017)

[1] In 2014 this slogan was declared in a letter written by the women’s working group of the national agroecology network (Grupo de Trabalho de Mulheres da Articulação Nacional de Agroecologia – ANA). (Photo credit: https://ctazm.org.br/img/noticias/noticia540/350.jpg)

[2] Quijano, A. 2007. “Coloniality and modernity/rationality” Cultural Studies21 (2-3):168-178. doi: 10.1080/09502380601164353.

[3] Lugones, M. 2014. “Toward a Decolonial feminism” Revista Estudos Feministas 22 (3): 935-952. doi: 10.1590/s0104-026×2014000300013.

[4] Crenshaw, K. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1 (8).

[5] Ngũgĩ, . T. 1986. “Decolonising the mind: The politics of language in African literature”. London: J. Currey.

[6] Mignolo, W. D. 2007. “Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality” Cultural Studies 21 (2-3):449-514. doi: 10.1080/09502380601162647.

[7] ¡Neither women nor land are territory for conquest! Photo credit: https://twitter.com/FeminismosMad/status/918524093963612160/photo/1Written by: Jessica Milgroom, supported by and with important contributions from an emerging feminist collective in Agroecology Now: Priscilla Claeys, Csilla Kiss, Stefanie Lemke, George McAllister, Nina Moeller, Jasber Singh, Chiara Tornaghi, and Barbara Van Dyck

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 844637